The Deeper Read

4: Sarah Gibbons

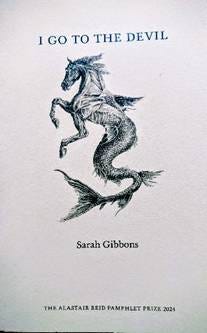

“And I Found His Nature as Cold Within Me as Spring Well Water” from I Go to the Devil, which won the Alastair Reid Pamphlet Prize in 2024 (Wigtown Festival Company, 2024). Please DM Sarah on Instagram for copies: @pulluppoet. Sarah co-founded and co-edits Black Iris poetry magazine.

Content note: sexual references

And I Found His Nature as Cold Within Me as Spring Well Water

He doesn’t always want you clean, yet each night

I walk into the loch’s brown-black waters

with my skirts knotted high over my waist.

I pinch the colour back into my cheeks

thinking of that first night – my bare shoulder

under his teeth, the rust mark of his kiss,

how he took my foot in his left hand,

and on my head, he laid his right.

Everything in between is mine

and we fell onto the dirt and tree roots

a coldness screaming through me, then the blood

rushing back, and all I’ve ever known

burning to greys and browns, the trees

charred blood vessels against the winter sky.

Sarah GibbonsThe Introductory Note to Sarah Gibbons’ pamphlet gives the context for this poem and its companions:

In 1662, in Auldearn, Nairnshire, Isobel Gowdie gave four apparently voluntary confessions of witchcraft. Her confessions are very different to others made at the time – in their dramatic invention and the richness and intensity of language she used.

The twelve poems in the book find their expression in a variety of forms, but half of them inhabit intense blocks. Interestingly, of these, four are thirteen-liners, a form once described by Peter Reading as “sonnets for the unlucky”; appropriate when dealing both with superstitions around witches and with those unfortunate enough to be persecuted because of such beliefs. Two, however, are full sonnet length: this, and “Death”, the final poem in the pamphlet, which imagines Isobel’s execution. Both could be read as love poems to selfhood.

The title of this poem is the longest of all of them; almost a word per line. Beginning with a conjunction, it appears to start mid-sentence, pulling the reader in and immediately invoking physical sensations. We can’t help but feel goosebumps as we imagine freezing water from deep underground, and even without the introductory note we realise that we are positioned in a time in this country before running water. The ambiguity of “Nature” creates tension. It sets the scene for the landscape imagery running through the poem, but also puns on ‘nature’ as “The vital or physical powers of a person” (OED Sense I.1.a.) or even genitalia (OED Sense I.3).

The first line also draws in the reader with its conversational tone; though it quickly, shockingly, transpires that this is anything but chitchat: “He doesn’t always want you clean, yet each night / I walk into the loch’s brown-black waters / with my skirts knotted high over my waist.” “He” is not named, though the generalness of “you” implies someone – or something – outside of a standard human interaction. This sentence, spread across the first three lines of the poem, rapidly takes us from the relatable to the eerie; from the familiar, wholesome coolness of the title’s “Well Water” to the frisson of desiring an unwashed body, of hoicking up skirts outside in the dead of night at a time when even showing an ankle was deemed improper for women. The masochism in seeking this bitter cold is heightened in “I pinch the colour back into my cheeks” – which can be read as another double entendre – but the speaker is making her own choice, confidently striding into the loch even if this is not what ‘he’ demands. ‘He’ begins the first line, but “I” begins the second: it is as if she is determined to feel something; even cold, even pain, in a time when her very body and its senses are proscribed.

The first two line endings – “night”, “waters” – embed us in the natural world, and the next six are rooted in the speaker’s body, desperate for sensation: “waist”, “cheeks”, “shoulder”, “kiss” ,“left hand” “right [hand]”. The lineation too begins as a very concrete parsing of the syntax of the first sentence, but in the second sentence begins to create tension with lies that annotate the syntax (Longenbach 69), making us wait between “bare shoulder” and “under his teeth”. As she thinks back to “that first night”, it seems she hardly needs to “pinch the colour back into my cheeks”, and the reader too flushes at the subtle eroticism of the description, now fully aware that they’re in for a poem which is “unsettlingly, seat-shiftingly sexy” (Maxwell 118).

That pleasure and pain are two sides of the same coin is skilfully elicited in the juxtaposition of “kiss” ending one line and “teeth” almost beginning the next, and in the implied burn of the “rust mark”; one of several heat images throwing the cold into relief. The BDSM dichotomies of submission and possession are evoked in “how he took my foot in his left hand, / and on my head, he laid his right”, also giving the sense that this is a supernatural lover with an all-encompassing reach. The imagery is both oddly tender and intimate as well as having biblical overtones. Jesus’ his feet were washed by Mary Magdalene and wiped with her own hair (Luke 7:36-50); and he in turn washed his disciples’ feet as an act of service (John 13:1-17). The laying of hands on the head is also a Christian blessing.

Boundaries are also set: the lover is stating a claim – “Everything in between is mine” – and the speaker appears complicit. Here is the volta of the poem; the whole of the sestet, the third and final sentence, rushing by in one enjambed breath:

and we fell onto the dirt and tree roots a coldness screaming through me, then the blood rushing back, and all I’ve ever known burning to greys and browns, the trees charred blood vessels against the winter sky.

We are once more literally rooted in nature, although the cold is not merely that of the water of the loch or the Scottish earth, but of the demonic lover himself, who is somehow both hot and cold, extreme sensation. Pain and pleasure are melded, the expert line break of “blood / rushing back” leaving that visceral noun hanging by itself, emphasised by the sight-rhyme with “root”, alarming us until “rushing back” brings our own rush of relief: the speaker is not bleeding, but experiencing overwhelming orgasmic sensation.

That she is altered by the experience is conveyed in the final two and a half lines: “all I’ve ever known / burning”, a worldview destroyed, but also perhaps recreated. We are back to a natural palette, the “greys and browns” echoing the “brown-black waters” of the second line; but its familiarity, and that of the “trees” and “sky” which end the final two lines of the poem, is irrevocably changed. These aren’t the dark colours of the winter Highlands, but the result of a cataclysm, “the trees / charred blood vessels against the winter sky”. It is as if the speaker is left lying on her back on the frosty ground, and we are staring up at the trees with her in a postcoital daze.

One of the great strengths of this poem is how Gibbons expertly weaves the imagery from top to bottom. We have colour: “brown-black” (2), “rust” (6), “greys and browns” (13). We have hot and cold physical sensations: “Cold” in the title, “bare” (5), “coldness” (11), “burning” (13), “charred” (14); and we have touch, mainly summoned through verbs: “pinch” (4), the bite implied by “teeth” (6), “kiss” (6), “took” (7), “laid” (8), “fell”(10). Both Isobel’s “outer and inner world”, in the words of the introduction, are thoroughly conjured: we believe her, and we can understand how her persecutors believed her too, leading to her murder.

We cannot know what Isobel herself believed; as Gibbons points out in the introduction, “The confessions could easily have been born out of trauma or torture or both. It has been speculated by some historians that she was a bard or storyteller in her own community”. I think the answer to the question of why she said what she did lies in the poem’s own intensity. If you lived in a time when to be a married woman was to be the property of your husband; when female sexuality, let alone the female orgasm, was unthought of; if all this was against the dour backdrop of an environment as unforgiving as the “religious extremism and persecution” of the society which inhabited it, you might just fantasise about having sex with the devil, and you might, in a desperate, nihilistic impulse, talk about it as the only way of being seen and heard.

*******

Something I like to do when reading poems is to see what poem is created by the end words, a kind of reverse golden shovel. Here’s the end word poem from this piece, keeping any punctuation, and in one block as per the original poem.

night waters waist. cheeks shoulder kiss, hand, right. mine roots blood known trees sky.

*******

Each week, I’ll share a poem of my own if I think I’ve one which chimes with the poem under discussion. Here’s “Opening the Witch Bottle” from The Emma Press Anthology of Contemporary Gothic Verse (2019). Like Sarah’s poem, it’s a sonnet in intention even if not in strict form: a love poem to persecuted yet resilient femininity, with a dash of sapphic attraction.

Opening the Witch Bottle ‘And they do say there be a witch in it, and if you let un out there’ll be a peck o’ trouble.’ - label in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford She’s waiting at the back of the museum forgotten in her bottle; stoppered up in witch-resistant metal. I can taste the stale air, her saturated space, and hear the silence, never quite complete, irked by muffled voices, passing feet. Its shine is tarnished; maybe she attempts to worry her way out where she can sense a weakness. Perhaps that’s what I am – I long to fit her curves into my palm and feel the simmer of her years of rage hopelessly molten in her silver grave. I want to break the bottle, snap the neck, free the desperate heat. Let out our breath. Suzanna Fitzpatrick

Works Cited

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Hodder and Stoughton, 1990.

Longenbach, James. The Art of the Poetic Line, Graywolf Press, 2008.

Maxwell, Glyn. Drinks with Dead Poets, Oberon Books, 2016.

Reading, Peter. Referring to Alan Brownjohn’s Ludbrooke and Others, Enitharmon, 2010.

OED. “Nature, N., Sense I.1.a.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2025, doi.org/10.1093/OED/7923443872. Accessed 28 January 2026.

OED. “Nature, N., Sense I.3.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2025, doi.org/10.1093/OED/1029605381. Accessed 28 January 2026.

This poem is one of my favourites from the pamphlet! It’s so beautiful, the way the words weave wicked imagery stays with you. It’s both haunting and powerful. I love the fact that she claims her own agency, no longer the victim

The image of tree branches as burnt blood vessels made me think of those grotesque tables used to teach anatomy to medical students centuries ago, where all the arteries have been dissected and flattened and gone brown. Eurgh. Such a visceral and sinister poem. Suzanna, your piece goes especially well this week - a modern mirror image. Fantastic analysis as usual!