The Deeper Read

3: Zakia Carpenter-Hall

“Animal Eden” from Into the Same Sound Twice (Seren, 2023), available from Seren.

Animal Eden It was the year of the viral video, nature coming out of hiding. We were supposed to believe that within weeks, animal lives had overwritten us with their joy and reckless abandon, instincts alerting them like radio waves signalling through the ether that humans were under quarantine and no one knew how long. Elephants who’d eaten Earth knows what, forgot about – the human dangers, perhaps consumed themselves into a stupor of corn wine and laid out in cultivated fields of tea leaves. I hate to anthropomorphize, but were those smiles that I saw on all of their faces? With the predators of the world gone gone – vanished – the prey had reached an Earthly nirvana, and it was heaven! Heaven on Earth! Heaven at last! And some of us humans, from the vantage point of our dark screens, felt so good for having seen it. Zakia Carpenter-Hall

What differentiates ecopoetry from nature writing? The most useful definition I’ve come across was given by Meryl Pugh in her Poetry School MA masterclass Writing the Environment: if one writes about oneself in the landscape, it’s nature writing, but if the poem’s scope goes further back and/or out to other humans, it tips over into ecopoetry. Zakia Carpenter-Hall’s poem “Animal Eden” is a case in point. The title is deceptively simple, almost reading like that of a children’s book: a dactyl (DUM-dee-dee) and a trochee (DUM-dee), both beginning with vowels, trip off the tongue like a nursery rhyme or something by Edward Lear. We think we know where we’re heading: something uncomplicatedly celebrating the glories of nature.

Irony, however, is already present. It is never – it was never – wise to take Eden at face value. It’s such a well-worn Abrahamic cultural trope: prelapsarian innocence and natural perfection. The story of Genesis preaches that humans ruined it for themselves, but maybe they were set up to fail: any parent knows that it’s a bad idea to point something out to your kids if you don’t want them to mess with it. Possibly the Old Testament God is the ultimate FAFO parent (Brown West-Rosenthal); in which case it was always a trap, never a true paradise.

The first line expertly sets the scene by deploying a wicked pun: “It was the year of the viral video”. We immediately know where we are in time: looking back, and looking back to Covid. I will put my hand up here: I love a pun; they are such an economical way to use language, and the play on “viral” shows how much heavy lifting a good pun can do in a poem. We were locked down because of a viral pandemic. We couldn’t do much other than stare at screens – which will reappear at the end of the poem – more irony being that a large proportion of humanity was already perhaps too much online, easily beguiled by memes spreading with pathogenic rapidity.

The first two lines of the poem are what Longenbach refers to as “parsing lines”. Syntactically complete, they “allow us to inhabit a syntactically complex argument more viscerally.” (68). They are end-stopped and biblically convincing. This was the year, and this is what happened: “nature coming out of hiding.” However, the third line belies this Old Testament certainty: “We were supposed to believe”. The line trips on “supposed”, landing heavily on “believe”, and now the readers do anything but: doubt sending us spiralling through eight lines which all run on, gathering momentum as they hurtle down the long block of the poem.

The “reckless abandon” of animals free of human interference briefly becomes our own as previous rules are “overwritten”, calling to mind Revelation 21:4: “for the old order of things has passed away” (NIV). Looking at the line endings, we go from “hiding” to “believe”, “lives”, “joy”, “instincts”, “waves”; the alliteration of the labio-dental fricative ‘v’ sounds adding to the va-va-voom. Two of these eight lines begin with present continuous verbs, keeping the poem’s accelerator firmly down: “alerting” and “signalling”. There’s big news, and the natural world is high on excitement; another pun, on “ether” as ‘drug’ as well as ‘atmosphere’, evoking this giddiness.

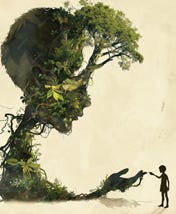

Carpenter-Hall sweeps her readers up in this excitement – no mean feat given that we all remember what lockdown was really like – only to bring us up short by reminding us that we’re not invited to this party: “humans / were under quarantine and no one / knew how long”; it is happening precisely because we can’t attend. When the cat’s away, the mice will play: the planet’s apex “predators” – in the sense not only that we have the capability to kill any other creature, but also that even when we’re not actively trying to do so, our actions cause the degradation of the environment – have been taken out of circulation by a pandemic most likely caused by the way we treat our fellow animals.

In this context, the words “and no one / knew how long” are menacingly double-edged. They capture the despair I remember feeling at having no idea what would happen, but they also hark back to the earlier imagined feeling of “joy” on the part of the non-human animals: our open-ended imprisonment becoming their open-ended liberation. Carpenter-Hall’s skill here is in allowing the enjambment to continue even as we are slapped by the line-breaks: “humans” hangs isolated but is not paused by punctuation, and the humans reading this are forced on into the “quarantine” of the next line. Juxtaposing “no one” as the next end word after “humans” is stinging, and again we are catapulted into the uncompromising uncertainty of “knew how long” in the next line. It reminds me of a satirical cartoon in which a human figure seeks to apologise to Gaia. She embraces them, but whispers as she does so: “[you] won’t be missed” (Deviant Art). The longest sentence in the poem has dragged us to its centre and brought us to our knees.

The ”Elephants” who end the next line are also “laid out”, but in a happier way, having “perhaps consumed themselves / into a stupor of corn wine”. This particular viral story was later debunked as fake, as I suspect Carpenter-Hall knows; all part of the Orwellian prolefeed distracting us while governments panicked (Nineteen Eighty-Four). We are back to the apocalyptic feel of the Book of Revelation, the true atmosphere of that time, and once again the lightness of the poet’s wordplay is brutally contrasted with a hard-hitting message: we are in a situation where things as we know them are breaking down. Even elephants, famous for their recall, are able to forget “human dangers”, while humans themselves are getting a taste of what might happen if we succeed in wiping ourselves out as a species. The unreliability of the ‘drunk elephants’ story is underlined by a vagueness in the detail; they have “eaten Earth knows what”. The switch to italics is significant, giving the feeling of an imprecation; but not the more familiar God knows what.

At the volta of the poem, God has been excised from Eden, along with humanity. The satire bites deeper as the speaker says “I hate to anthropomorphize”, then proceeds to do exactly that: “but were those smiles that I saw on all / of their faces?” The end words of the next four lines tell their own story: “predators”, “vanished”, “nirvana”, “Earth”. It’s as if a gospel choir is singing refrains of praise, punctuated with bold exclamation marks: “and it was heaven! Heaven on Earth! / Heaven at last!”. But “nirvana”, hanging on the end of a line, interrupts the heavenly chorus. Not only does it take us out of the Christian hegemony, it reminds us that heaven, like Eden, is not all it seems; in Buddhism, “Nirvana was not regarded as a place … but as a state of absence, notably the absence of suffering” (Lopez).

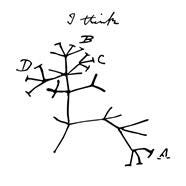

By adding “nirvana” to the repeated use of “heaven”, Carpenter-Hall devastatingly drives home the suffering that human actions cause, directly or indirectly, to our fellow creatures. Meanwhile, where is humanity? In a hell on Earth of our own making, glued to “dark screens”; our separation from the natural world both begun and completed by the industrial revolution and technology. Is it a comfort that “some of us humans” see and celebrate the benefit to nature that our incarceration has provided? Or – given that we have already ascertained that some of these “viral videos” were fake – is even this emotion thrown into doubt? The poem’s final pun on the “[ad]vantage”, evolutionary or otherwise, of humanity’s position in the tree of life – and here we think of Darwin’s diagram, not the Edenic tree of knowledge – is a particularly mordant finale to this far-reaching ecopoem.

*******

Something I like to do when reading poems is to see what poem is created by the end words, a kind of reverse golden shovel. Here’s the end word poem from this piece, keeping any punctuation, and in one block as per the original poem.

video, hiding. believe lives joy instincts waves humans no one Elephants what, dangers, themselves out leaves. anthropomorphize, all predators vanished – nirvana, Earth! humans, screens, it.

*******

Each week, I’ll share a poem of my own if I think I’ve one which chimes with the poem under discussion. Here’s “Redwings”, which was Highly Commended by Gerard Smyth in the 39th Annual Goldsmith Poetry Competition 2023. I wrote it staring out of the window during the early 2021 lockdown. Like “Animal Eden”, it is ostensibly about wildlife but really saying something about the human animal; in this case, attitudes towards migration.

Redwings

Movement shakes the frozen chandelier

of the silver birch, and I look up,

hopeful for birds. I smile to see them

teetering on branches: thrushes. No,

redwings, migrants: a dogged flock

flown non-stop from Scandinavia –

five hundred miles of storms. Many drown,

but these have made it here, rewarded

by next door’s Sorbus. One of them plucks

a pale pink berry, holds it briefly

in beak-tip, tilts and swallows. I feel

the crisp bolus of fruit, chilly air

stirring striated feathers, the need

compelling flight. Nature wastes nothing

in desire: they come because they must.

Suzanna FitzpatrickWorks Cited

Brown West-Rosenthal, Laura. “What Is FAFO Parenting? Unpacking the Trend Parents Are Buzzing About.” Parents, 13 February 2025, www.parents.com/what-is-fafo-parenting-unpacking-the-trend-11678790. Accessed 21 January 2026.

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Hodder and Stoughton, 1990.

Deviant Art. “Self-Centered Humans.” Twisted Sifter, 18 June 2011, twistedsifter.com/2011/06/comic-strip-of-the-week-26/. Accessed 20 January 2026.

Longenbach, James. The Art of the Poetic Line, Graywolf Press, 2008.

Lopez, Donald S. “nirvana.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 31 October 2025, www.britannica.com/topic/nirvana-religion. Accessed 20 January 2026.

Macfarlane, Ross. “Tree of life.” Wellcome Collection, 31 May 2022, wellcomecollection.org/stories/tree-of-life. Accessed 21 January 2026.

Orwell, George. The Penguin Complete Novels of George Orwell, Penguin, 1983.

Pugh, Meryl. “Building Blocks of Form: Writing the Environment.” Masterclass 1.9, 12 March 2024, The Poetry School. Seminar. Notes taken by me.

Sewell, Bethany. “Fake Wildlife Photos Flood Internet During Global Lockdown.” Nature TTL, 26 March 2026, www.naturettl.com/fake-wildlife-photos-flood-internet-during-global-lockdown/. Accessed 20 January 2026.

World Health Organization. “WHO Scientific advisory group issues report on origins of COVID-19.” WHO, 27 June 2025, www.who.int/news/item/27-06-2025-who-scientific-advisory-group-issues-report-on-origins-of-covid-19. Accessed 20 January 2026.

a great poem to flex the muscles to an even deeper stretch, and its another great work Suzanna! x