The Deeper Read

5: Glyn Maxwell

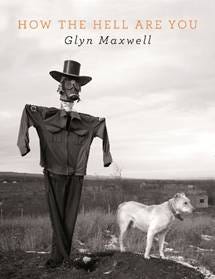

“The Ledge” from How The Hell Are You (Picador, 2020), shortlisted for the 2020 T. S. Eliot Prize. Available from Picador.

The Ledge for Alfie Woken again by nothing, with this line already at my back, I thought of you at twenty, as you are – which passed somehow while I was staring – thought how yesterday you said you wanted to be young again, which left me with this nothing left to say that’s woken me. You are, you are – what else does father wail to child – though wailing it he’s woken with six-sevenths of the night to go – you are – look I will set to work this very moment slowing time myself, feet to the stone and shoulder to the dark to gain you ground – if just one ledge of light you flutter to, right now, rereading that. Glyn Maxwell

In his Substack, Silly Games to Save the World , Maxwell occasioned no small debate last year by suggesting that poets – certainly those studying with him on the Poetry School MA in Writing Poetry – could consider ditching titles for poems, arguing:

“It casts light – or shadow – over everything that follows … the title should come to you last, when you have a sense of what you just wrote. Even then, don’t use it. Even if you thought of it last - after the draft was written - placing it at the head of the poem falsifies the action of the heart or mind. It implies a level of control or determination that is not the case.”

Interestingly, the title of this poem does come at the end, in the penultimate line; looping back to the start and casting retrospective light on what we read there. Glyn knows – since I did study with him on the Poetry School MA – that I’m more of the opinion that when a title works well it is a hand held out to the reader; after all, as he himself says: “The reader walks with you”.

This poem’s no-frills title offers a hand and immediately pulls us to a place we know is precarious, without giving too much away. A ledge is narrow, usually high; one dropped consonant away from the edge. It’s a place of discomfort, borne out by the first line and a half: “Woken again by nothing, with this line / already at my back”. We are immediately in the realm of insomnia – repeated insomnia, as implied by “again” – the poem insistent, “already at my back”. The image is less that of a lover curled around the speaker than of something nagging, and something nags at us too as we read. Maxwell can be relied upon to know the canon, and here is Marvell, pleading with his “Coy Mistress”: “But at my back I always hear / Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near” (21-1). This is a sonnet, but the speaker isn’t a lover cajoling his mistress; instead he’s a father speaking to his child, who is already a young adult.

Time has “passed somehow”, but the genius of this poem is that it mentions the fugit in line 3, but delays naming the tempus until line 11, in which the speaker determines that he will work at “slowing time”. This reminds me of something Maxwell said in an MA seminar last year: “If you talk about something that isn’t there in a poem, it is there, because you’ve mentioned it. So if you talk about absence, absence becomes a solid: an absence of absence” (Workshop 5) The fact that time is resolutely unnamed until the sestet of the sonnet means, rather like leaving out a title, that the readers can come to their own conclusions.

They do so as meditatively as the speaker as he leads them through a sentence which takes up half the poem until midway through the seventh line, all lines bar one enjambing. There’s plenty of punctuation in the form of commas and dashes as we weave in and out of clauses, but only once at the end of a line. The metre, however, is pure sonnet: strictly ten syllables per line, and often iambic (dee DUM), although Maxwell has too practised an ear to stick to that for the sake of it. I could go full-on prosody at this point, but we’d be here all day, so instead I’ll simply scan the first two lines as an example, stressed syllables in bold:

Woken again by nothing, with this line already at my back, I thought of you

The first line freestyles with a trochee, an iamb, then the promise of three more iambs: DUM dee, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM. Except that’s not really how we’d speak, landing so heavily on the conjunction “with”, so instead it’s a trochee, two iambics, a pyrrhic and a spondee: DUM dee, dee Dum, dee DUM, dee dee, DUM DUM. Then the second line snaps back into classic iambic pentameter: dee Dum, dee Dum. Humans, do you think you can escape time? You can’t: its beat marches in these iambics, in the padam of your heartbeat (Piaf/Minogue).

Counterpointed against the pulse of the words are the line breaks, their audacity ramping up the tension from the start, beginning with the boldness of ending the first line on the word “line”. Every line in the first half of the poem breaks mid-thought, creating the foreboding awareness that one day we too will be interrupted in whatever we’re doing for the last time. The readers are kept on their toes, constantly interrogating. What about “this line”? It’s “already at my back”. Who is “you”? Someone “at twenty”. How has something “passed somehow”? It was “while I was staring”. What happened “yesterday”? The ‘you’ “said you wanted to be young again,”. Here we have the only end-stop in this sentence, leading to the most fiendish of its clauses: “which left me with this nothing left to say / that’s woken me.” The iambics smooth our way through it, but we stop, as does the speaker. We’re used to the phrase “nothing left to say”, however, by adding “this”, Maxwell does more than make it iambic. The speaker does have something to say: it’s “this nothing”; an absence of absence again. It’s something because it has “woken me” – the heart of the poem reminding us of its first word – yet it’s nothing, because nothing any of us can say can halt time.

The poem pivots at the volta on precisely this breakdown of language, the speaker helplessly repeating himself: “you are, you are – what else / does father wail to child”. There is humour in the idea of a twenty-year-old wanting to be ‘young’, though we can understand the nostalgia for childhood occasioned by a growing realisation of what adulthood entails. But this humour is bleakly underpinned by hints of role reversal: it is the father who “wails” and repeats, reminiscent of Jaques’ speech from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, encompassing the seven ages of a human life from “the infant, / mewling” to “second childishness and mere oblivion” (II:VII 139-66). The speaker may have woken himself up with “six-sevenths of the night / to go”, but the implication is that he has rather less than six-sevenths of his life left; and in this breathless second half of the poem, all one sentence again, even this is slipping away.

Perhaps he comes to the same conclusion, because with a prayer-like third utterance of the refrain “you are”, as if to assert this truth, he decides on a plan of action: “look I will set to work / this very moment slowing time myself,”. He is in such a rush to do so that he doesn’t even pause with a comma after “look”, as one might expect; and once again the other line endings of this sentence run on unpunctuated with just one exception: the comma after “myself”. I will do this for you myself, says the speaker to his child; I will do anything to help you, “gain you ground”, even if it’s a Sisyphean endeavour, as evoked by “feet to the stone and shoulder to the dark”. Here is another example of breaking the expected metre to make a point: by reversing the iamb to a trochee at the start of the line then letting it revert to iambs in the second half, the emphasis falls on “feet”, “stone” and “dark”. This is the sheer physicality of parenthood, of existing in a fallible human body. We can feel the coldness of the stone, and we can feel the impossibility of physically shoving away the “dark”, either of night or of our mortality; the half-rhyme with “work” emphasising the challenge of both.

It may be impossible, but it’s worth it “if just one ledge of light / you flutter to, right now, rereading that”. The adult child is fledging, and we sense their vulnerability in the delicate alveolar plosives – ‘t’ – of “flutter”. What I think of as ‘head’ verbs are so dominant in this poem – “thought”, for example, is used twice (2, 4) – that ‘body’ verbs really stand out, especially in their yearning vowel sounds. There’s obviously the repeated “woken” (1, 7) and “wail/wailing” (8), their ǝʊ and eɪ sounds evoking dismay; but the same sounds are repeated in the second half of the poem in “slowing” (11) and “gain” (13). The father is doing his slow, painstaking work to give his child the chance to “flutter” quickly to safety, even if it’s no more than “one ledge of light”.

“You master form you master time” (On Poetry 45) is one of my favourite Maxwell quotes; although tellingly, I always misremember it as ‘you control form, you control time’, which possibly tells you everything you need to know about me; I’ve written here on Substack for Consilience Journal on poetic form and trauma. “Poems must be formed in the face of time, as we are” (On Poetry 46); T.S. Eliot’s fragments shored against ruins (430). The compact sonnet is certainly the right form for this, being “Something you can utter in one long convulsive breath” (Brown). This is both gasp for air and shout; a cry simultaneously of love, despair and hope.

I’ll finish by suggesting we look carefully at what Maxwell does with the tenses in this poem, for this above all proves his mastery of time. “Woken”, at the very start, is simultaneously in the past and the present, then we stay in the reflective past with “thought” (2), flip in line 3 between present – “are” – and past – literally, “passed” – and stay in the past with “thought”, repeated in line 4. Come line 5 we flip again, this time past to present – “wanted”, “be” – then back to the past with “left” twice in line 7. At the volta, the speaker clings to the present, repeating “are” in line 7, and moving from the present “wail” to the present continuous “wailing” in line 8. Line 10 brings in the future for the first time with “I will”, and the speaker’s determination sees him do away with verbs and tenses entirely in line 12; there is nothing but a grappling with nouns and prepositions. The last line of the poem performs the final temporal sleight of hand: “you flutter to, right now, rereading that.”. The present tense of “flutter” is emphasised by “right now”; but the final verb, “rereading”, is somehow past, present and future all at once. It is also Maxwell’s winked invitation to us: go back, read this again, rewind time. We can do that with words, though we can’t do it with anything else.

*******

Something I like to do when reading poems is to see what poem is created by the end words, a kind of reverse golden shovel. Here’s the end word poem from this piece, keeping any punctuation, and in one block as per the original poem.

line you somehow yesterday again, say else it night work myself, dark light that

*******

Each week, I’ll share a poem of my own if I think I’ve one which chimes with the poem under discussion. Here’s “Fledglings”, the title poem from my first pamphlet of the same name, published by Red Squirrel Press in 2016. It shares both a soundscape and flight imagery with Maxwell’s poem; though being about a newborn, time passing is not yet on the horizon, and this speaker resolves not to slow time, but to ride it with her child.

Fledglings I stroke the tiny kites of your shoulder blades, imagine wings. Gingerly I stretch my own. It’s been so long since I trusted them. As your nestling’s down gives place to feathers, I’ll re-learn flight with you. Let’s stand, teeter-happy, brink-thrilled, taste the wind. And we’ll soar, my darling. We will soar. Suzanna Fitzpatrick

Works Cited

Brown, Laynie. “On the Elasticity of the Sonnet and the Usefulness of Collective Experimentation.” Poets.org, 2 September 2010, poets.org/text/elasticity-sonnet-and-usefulness-collective-experimentation. Accessed 4 February 2026.

Eliot, T. S. “The Wasteland.” Collected Poems 1909-1962. Faber, 1963, p. 79.

Fitzpatrick, Suzanna. “Safety in Chaos: Poetic form as a means of processing trauma.” Consilience, 14 July 2025, open.substack.com/pub/consiliencejournal/p/safety-in-chaos?utm_campaign=post-expanded-share&utm_medium=web. Accessed 4 February 2026.

Marvell, Andrew. “To His Coy Mistress.” Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44688/to-his-coy-mistress. Accessed 3 February 2026.

Maxwell, Glyn. On Poetry. Oberon Books Ltd., 2016.

---. Workshop 5, 28 January 2025, The Poetry School, London. Seminar. Notes taken by me.

---. “Stop Giving Poems Titles.” Silly Games to Save the World, 6 April 2025,

glynmaxwellgmailcom.substack.com/p/stop-giving-poems-titles?r=2q9p8f&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true. Accessed 3 February 2026.

Minogue, Kylie. “Padam Padam.” YouTube, 18 May 2023, youtu.be/p6Cnazi_Fi0?si=6eahUOiity6XGxKg. Accessed 3 February 2026.

Piaf, Édith. “Padam, padam.” YouTube, 30 November 2015, youtu.be/xXqLj7X1WDU?si=AxAJpDykaF6sBeUI. Accessed 3 February 2026.

Shakespeare, William. “As You Like It”. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. OUP, 1994, pp. 627-52.

As I have said before this deep dive is brilliant and particularly this time unravelling the master of form and time and explaining every nook and crevice of this great poem is a gift to us - thank you Suzannah.

I’m really enjoying this series, Suzanna. You make so many excellent points about the poems that I wouldn’t have noticed on my own, like the “head-verbs” and “body-verbs”, and the comparison to Marvell.

Also, love the picture of an alarm clock stabbed in the heart by a STOP sign. I can relate.